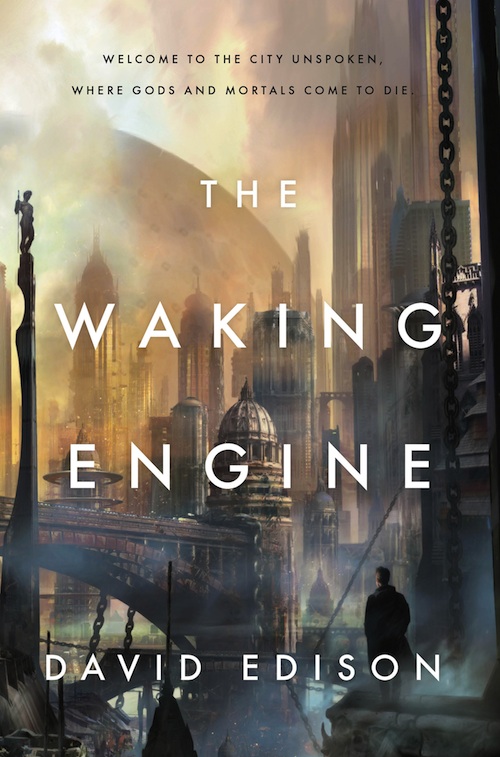

David Edison’s debut novel, The Waking Engine , is available February 11th from Tor Books. Read the first chapter before continuing with chapter two below!

Contrary to popular wisdom, death is not the end, nor is it a passage to some transcendent afterlife. Those who die merely awake as themselves on one of a million worlds, where they are fated to live until they die again, and wake up somewhere new. All are born only once, but die many times… until they come at last to the City Unspoken, where the gateway to True Death can be found.

Wayfarers and pilgrims are drawn to the City, which is home to murderous aristocrats, disguised gods and goddesses, a sadistic faerie princess, immortal prostitutes and queens, a captive angel, gangs of feral Death Boys and Charnel Girls… and one very confused New Yorker.

My friend Lao-tzu says, “Darkness within darkness. The gateway to all understanding.”

Of course Lao doesn’t mean the absence of light, you’ll see that. No, all of his friends appreciate that Lao-tzu finds freedom in that ultimate ignorance we all must face eventually: death. But I was raised to believe in a god who died for my sins. Of course I never believed in sin, and when death never came I had nothing left to pretend to believe.

It is like that everywhere, you’ll discover. Names for gods that never existed or who lied about what they were, or disappeared ages and ages ago. Tedious ends to tedious pedagoguery, but there you have it.

My friend Lao-tzu also says, and I think him terrifically wise for pointing it out, that names are a waste of time. “The unnamable is the eternally real,” he tells me, and I do think he’s right about that. “Naming is the origin of all particular things.” This means something a little profound, obviously, because it suggests that “things” can never be real.

Was that ever truer than in the case of worship?

Who is Christ on the cross to me now? I haven’t seen him at any of the parties.

—Truman Capote, Better Birds

Sesstri Manfrix sat at her desk, watching the ink dry on another page of another journal and holding her quill in her hand like a poisonous spider. Everything was so different here. The City Unspoken was like nowhere she’d ever lived, and as much as the filth and decay offended her senses, she knew she’d make more discoveries here than in any library she’d ever scoured. There was enough history and unspeakable age here to fill a thousand ruined cities and still have mystery to spare.

It was a historian’s nirvana. Or her nightmare.

And then there was Asher.

When she met him, murdering books in a library, he’d been awkwardly formal, and Sesstri had been too keen to work out the etiology of his colorless skin to notice the intensity of Asher’s gaze. Yes, she would accept payment to help him with his research. Yes, she would be interested in knowing the subject matter. Yes, she was well versed in any number of disciplines pertaining to metaversial anthropology, and panspermic linguistics, and no, she did not mind legwork. She would like to hear about what concerned him, and no she felt very safe in the company of a strange man—though those last had been a lie and a lie of omission, respectively. Of course Sesstri felt safe; she bristled with hidden knives, razors, pins.

Sesstri had learned to mistrust reactions based upon her beauty. In her last life, she’d discovered old age with a kind of relieved exhaustion. When she’d walked into this house, shaky on the arm of the curly redhead who’d found her, who’d rented her the home, and she had gotten a look at herself in the mirror, she’d almost screamed. In the weeks she’d worked with Asher, poring over worm-eaten texts that all but crumbled in their fingers, Sesstri had caught glimpses of that infatuated look in the gray man’s eyes, and knew that it would only be a matter of time until he—and by extension, she—had to deal with it.

But he’d trusted her, enough to finally relent and show her what frightened him so. Asher took her to Godsmiths, crossing one of the city’s ever-present gargantuan chains, secured as a catenary bridge across the sundered earth of the gloomy district, and Sesstri wondered what the ramshackle ruin of a neighborhood contained that could possibly animate Asher with such fervor.

In Godsmiths they found the svarning. Just the smallest, lightest touch of it, but enough for proof-of-concept. The day had been sunless, a bright white sky empty except for the constant moonrise of the Dome to the east, its inner glow dimmed by the day.

“There is a word for this.” He pointed to the emaciated women, standing rigid at their doors, staring toward the Dome. The stains on their trousers or beneath their skirts hinted at the length of time they’d been standing there. Many had milky eyes because of dead corneal tissue; they hadn’t blinked in days.

“There is no word for this.” Sesstri stood by the circle of dancing girls, scribbling notes on her pad as fast as she could. There was no point trying to intervene; that was not their purpose. But it was difficult for her to see the page; although the air was clear, her vision wavered, as with tears or intense emotion, though she had neither.

Asher told her the word.

The little girls’ hands bled where their nails dug into one another’s palms. They skipped with an exhausted gait, but their eyes were full of cheer. Horrible, agonizing cheer. They had moved beyond joy and pain into an extremity of feeling that conjured its own toxic magic. That was the svarning. Little girls who danced to the point of death and beyond, and beyond, and beyond.

But those were not the stakes. Braided tits of the horsemother, those were an example of the bare minimum casualties, not even a full outbreak. Asher promised that the svarning would evolve, not just from person to person but changing in aspect as it grew. When or if that mania seized the city, if it spread throughout the worlds… would the metaverse detonate in some kind of psychic supernova? Or would the cogs of existence run ever hotter, ever faster, and its fevered inhabitants spin on in an ever-more-tortured eternal life?

The plan was that Cooper was supposed to be someone special. The plan involved someone special leading them to a solution, somehow, somewhere. That’s what Asher had promised her, however he knew, and she had promised to find and identify this special someone.

So why had she lied?

Sesstri stared out the window, over papers and books, to the towers of abandoned districts that burned like candles of stone, glass, and steel. Though they burned night and day, they never fell, and were held by undead masters who manifested as clouds of roiling darkness streaked through with red lightning, an ever-brewing storm above ever-burning skyscrapers. The gangs that worshiped undeath like a god had run those districts even before the government withdrew into the Dome—but now whole sections of the city seethed with black-clad youths engaged in constant battle against one another and the City Unspoken. Despite the untapped trove of history she knew lay within those impossible towers, Sesstri hadn’t ventured anywhere near them, yet.

She’d learned from her contacts in Amelia Heights, from the artists and the artisans who still clung to their homes there, about the power of the forces martialing around those towers. The gangs, collectively called the Undertow, had acquired something since the prince’s absence, some power or leverage that allowed their influence to grow: the liches, undead spellcasters with human intelligence and ambition, had either grown in number or flocked to the City Unspoken from elsewhere, filling a power vacuum. Their thralls—well, the youths had swelled in numbers to an even greater degree, and while the Death Boys and Charnel Girls weren’t undead themselves, they’d tasted something of it, and it gave them power. The names they’d given themselves along rudimentary gender lines, Death Boys and Charnel Girls, they seemed silly names to her, but as a collective the thugs posed a real threat to the declining stability of the city.

And yet, the Undertow were only a symptom. The Dome, which dwarfed even the flaming towers and smoldered with a different light— gold and green, full of life—it worried her far more than a little army of children and monsters. Armies were finite. The damage to the City Unspoken, decapitated from its leadership, was much harder to quantify. Anarchy during crisis yielded nothing good.

She didn’t quite trust Asher, despite wanting to. And she wanted him, despite not trusting herself one bit.

If only she hadn’t lied about Cooper. If only Asher had possessed the good sense not to trust her, or the kindness not to take the boy to the Guiselaine and leave her to ponder her error. She didn’t understand the pallid man—maybe that was why she felt so odd in his presence, as if she weren’t quite as brilliant as usual—more spiteful, less gracious.

She’d told Asher everything but the crucial fact. She’d identified from the construction and branding of Cooper’s clothing alone that his entire culture was childborn. There was a certain solipsistic air about civilizations that were illiterate to their larger metaversial context—her homeworld had been no different in that regard.

But if Asher knew that Cooper had a navel… He’d be furious, but she’d been certain she would think of an answer before they returned. Nobody who’d died had a navel, only the childborn, for as long as they lived in their first flesh—only they had that scar, that connection to their mother and their first, only, literal birth. Sesstri put her hand to her own belly, flat and hard and perfectly smooth. She didn’t like to think about her navel, or how she’d lost it.

But the more Sesstri considered the question, the less certain she grew that there was an answer to Cooper’s arrival—or at least, no answer that she could uncover with mere perspicacity. No, the more she considered it, the less sense Cooper made. A navel. He was an erratum, to be sure, growing ever more erratic, and Sesstri’s conviction that Cooper was worthless faltered.

What would she have done if Asher hadn’t left the room before she’d stripped the foundling? How could she admit to him that she had no idea how such a thing was possible? To commute between worlds without death as your oarsman was impossible for lesser beings. For a godlike being—one of the First People—or an incredibly powerful mortal, certainly, but for a childborn young man like Cooper to wake up intact in his original body, the body of his childbirth? Sesstri couldn’t explain that.

And she had no intention of telling Asher the truth until she could.

She walked the empty house, worried. Sesstri never worried. And she never lied to a client. So she was doubly distressed as she climbed the stairs of her little house south of Ruin and the Boulevard of Wings, staring at the vase of wilted foxgloves that sat by the landing’s small oriel window. Her day had devoured itself this way, aimlessly, and nothing could be less typical of Sesstri Manfrix than aimlessness.

Of course it was more than Cooper—there was the svarning, which she could feel prickling at her skin and getting stronger every day. The Dying pilgrims were growing in number; they found it harder and harder to Die, and that worried Asher. As it should—the mass Deathlessness brought on a malaise that was partly psychological and partly paranormal, and entirely unpredictable. It infected the young as easily as the old, as if the air itself were tainted by the rotting souls of those who should be Dead. Svarning: a word from a language with no known descendants that was either ancient beyond reckoning or entirely fictional. If the word was real, Sesstri had translated its meaning as lying somewhere between “heartsick” and “drowning,” and occasionally “illuminated,” although the degree to which those interpretations were valid would be open to debate.

Death. Undeath. Power. Svarning. Sesstri wasn’t disturbed by any of that—it was all grist for the mill of her mind. All part of her work. Like many of the metaverse’s persevering geniuses, Sesstri Manfrix hadn’t let the interruptions of death disrupt her studies. Instead she’d expanded the scope of her investigations to include an existence punctuated by periodic transmigration—through death—and found that what she lost in continuity she more than recouped through longevity. Her second life had been fortuitous: peaceful and providing access to many notes and records of the larger metaverse of which she had been so ignorant throughout her first life. In the reality that called itself Desmond’s Pike, Sesstri had raised a family and researched the metaverse and its primary method of transportation: dying.

What’s death to a historian who never dies? What’s history to an eternal woman? Even after apocalyptic war came to Desmond’s Pike, with gold machines that fell from the sky and disassembled the world one atom at a time, Sesstri knew that she’d have the luxury to answer her questions at her own pace. Now her limitless learning appeared threatened by the rise of the svarning. So she’d solve it. One woman against a metaphysical illness that threatened all universes? Of course she could solve it.

Other questions were less forgiving. What’s love to a woman who’d never met her equal? What, for that matter, is love? The browning foxgloves didn’t answer; they only raised further questions. Why hadn’t she refilled the water in the vase?

Oh, Asher.

She’d lied because Asher frightened her, and Sesstri had decided at a young age never to be frightened of a man. Her father the Horselord had taught her that much, at least. She would solve the problem of Asher after she’d unraveled the threat to the metaverse.

The matter at hand: Cooper hadn’t traveled here by himself; he smelled of no grand magics and heralded no invading army or technological superiority. He was as mundane as it got. That left few options, all of which pointed to the one subject that made Sesstri uncomfortable: the First People. Gods, the ignorant called them. She had no use for such charlatanism, and while there was no arguing the existence of any number of beings who were—or chose to remain—unfathomable to humankind and the other races of the Third People, there were no true gods in the absolute sense of the word, merely players of a larger game, with a wider reach and deeper pockets. They might be beyond mortal ken, but that was due to mortal limitations rather than a MacGuffin called divinity. Name them what you will, Sesstri felt, but worship was a waste of good incense.

She packed her satchel. She might as well get some work done, and as long as she had worship on her mind, she could catalog some more of antidogmatic stories told in and about the City Unspoken. She could sort through drivel about gods and goddesses and find truth there, somehow.

What truly irritated Sesstri was the idea that any knowledge might be barred to her because she was somehow lesser, and this struck her as the ultimate copout. Not to mention insulting. Give me a week in the library of a goddess, she knew, and I’ll come out with conclusions. Give me an hour with a demiurge and I’ll return with citations and cross-references that are perfectly analogous to any other quarter of historical or empirical study.

What’s a god but a man behind a curtain?

Curtains burn.

For a while after Asher left him in the Guiselaine, Cooper didn’t really pay attention to where he wandered. Dead, abandoned, alone, and lost— it made his chest tight and his eyes too watery to see well. By the time he could breathe, he’d found himself hassled on a dusty thoroughfare where everyone seemed to be in a hurry and nowhere seemed an acceptable place to be. He found an exception in a clearing at the side of the road, where pedestrians went out of their way to avoid what looked like a wounded airman from the First World War, hiding in a barrel of beer.

“Hi there,” Cooper said, peering down into the beer. “Are you, by any chance, from a place called Earth?”

“Nerp,” the pilot bubbled.

Cooper nodded, aiming for sanguinity and missing. “So you’re not a fighter pilot from the First World War? The Great War, I guess you would have called it, only you wouldn’t have, since you’re not from it. From there. From Earth.”

“Ah. I see.” He tried again. “It’s just that you’re dressed a lot like a fighter pilot.”

The man lifted his head out of the beer enough to shake his head. “Oh, I’m a fighter pilot. That’s why I’m dressed like one. I’ve just never been to Erp.”

“Earth.”

“Sky!” the pilot cheered. “I like this game. Your turn.”

“Um.” Cooper nodded again. “Why are you hiding in a barrel of beer?” “I’m not hiding.”

“You’re not?”

“Nerp. I’m drowning myself in beer. It’s the thing to do.”

Cooper almost pointed out that drowning oneself in drink was not supposed to be a literal thing, but he remembered Asher’s admonitions and checked himself. Perhaps, in the City Unspoken, death by beer was perfectly acceptable. That wouldn’t be the weirdest thing Cooper had learned today.

“Where do the lost go?” Cooper asked the pilot, not intending to sound like a confused fortune cookie. The man sank a little, and his answer was not intelligible.

“I’m sorry, I don’t quite follow.” Cooper squinted his face and squeaked out an imposition: “Might you be willing to stop drowning for just another moment? I really am very, very lost.”

With a sigh of superheroic effort, the pilot stood up in his barrel, raining lager onto the cobbled gutter, pointed down the road, and said: “Bridge. Music. Mountain.” And then, as if to clarify: “Over bridge, through music, under mountain.”

Then the pilot replaced his aviator’s goggles, tugged at the red beads clustered at his suntanned throat, and submerged himself in beer again. One hand emerged from the pale yellow foam like a parody of the Lady of the Lake, holding an oversized beer stein brimming with ale. Cooper didn’t stand on ceremony—he took the proffered pint and walked away as swiftly as his feet would carry him. He had the pint halfdrained by the time he rounded the bend. Afterlife beer was stronger than he’d expected.

So when he stumbled, drunk, from the bridge built of giants’ bones and reinforced concrete, Cooper hoped he saw what the beer-marinated fighter pilot with the red beads had described. He faced a pointed hill, odd and steep, where the crust of the city had been pushed up like an anthill or a volcano, wrinkling the weft of the architecture around it.

A road led down into a park, then continued on below and through the tall hill, which Cooper supposed might be the mountain in question. In the distance the Dome loomed, a planetoid moments away from collision.

Cooper stumbled toward the park, a nestled vale of cypress and stranger trees, rangy blue-tipped eucalyptus, curly willows whose curls spilled upward. Beyond the park, the road dipped beneath the mountain, dark as a funnel spider’s web.

An overgrown drum circle seemed to have set up semipermanent camp in the park—dominated by a profusion of musicians and singers who sat atop or leaned against a length of massive chain that seemed more or less draped across the park. The tolling of bells that had followed him all day grew louder, but didn’t seem to dampen the orchestral spirit of the gatherers. An odd little musical collective played a dozen tunes at once and each drew its own audience, using the oversize chain links as performance spaces and stages, or for seating.

Away from the tidal force of the streets of the Guiselaine, Cooper found the presence of mind to closely examine the throng for the first time. The people who arranged themselves according to the links of huge chain seemed plucked from a dozen countries and eras. A dozen worlds. A mule-eared busker juggled pomegranates in one hand while playing a brass horn with the other, and he winked at Cooper with overlarge eyes as he passed. A few chain links down, a trio of women with bared breasts and faces painted like Chinese princesses arranged sheaves of music on the shelves of a kiosk, singing in three-part harmony.

What are those chains for? Cooper mused. He’d seen them from Sesstri’s rooftop running through canals and alleyways. They cut through the city, but whatever purpose they might once have served seemed forgotten, or at least buried.

Cooper burped loudly and tasted beer—a shaven-headed man with a chest scrimshawed in scars clapped and gave him a thumbs-up before going back to pounding out rhythm on the skin of his drum. Cooper gawped at the muscles dancing in the man’s torso; in his stupor the scars seemed to wink like the faces in the bark of an ancient tree. One of the painted princesses broke away from her sisters to rest her hand upon the scrimshawed man’s shoulder, leaning over from behind to kiss his cheek. The rough-looking man leered at her appreciatively, still drumming, and rubbed his beard against her peach nipple, inhaling the perfume of her breasts with a familiar relish.

“Beautiful, ain’t she?” he asked when he saw Cooper look a moment too long.

“Oh. Yes.” Cooper scratched his head. “Absolutely, yes.”

Taking in his surroundings with an equanimity only the inebriated can command, Cooper made his way through the crowd of listeners and performers. Once he would have given an arm to step through a doorway into an otherworldly carnival, but now all he could do was look for an ATM sign. It was a compulsive reflex in a head not quite as prepared for total world-upheaval as it might once have fancied itself.

Shaking off his ghosts, Cooper thought that he hadn’t intended to get drunk, but couldn’t convince himself that he wished he were sober. It was that damn fighter pilot’s fault, anyway.

Under mountain. Cooper looked up to see the rise of tilted buildings climbing up the near distance. It seemed that all the houses and rookeries could come sliding down on all their heads at any moment. The lane dipped at an easy angle, and as he left the music behind, Cooper smelled incense and dinner being fixed within nearby homes. Garlic, onion, meat—and from the descending path he followed, sandalwood, cedar, amber.

The steps were carved in a shallow decline on either side of a wide ramp intended for handcarts and rickshaws, and Cooper stumbled past townhouses and tenements in a succession of levels until the narrow ribbon of the sky was crisscrossed by a web of supports and rafters. Light spilled from open windows and the air chimed with the sounds of domesticity; he heard women argue with their husbands and children—children, of all things, the first sign of any recognizable natural order he’d seen in the City Unspecified. Cooper had assumed the city to be filled with old souls and death-seekers, but of course that wasn’t true. Not entirely. Life and death, side by side, formed the meat and sinew of the city, and gave rise to all sorts of things, grisly and familiar— mule-eared buskers, screaming toddlers, and bread dough rising in the oven of a top-heavy house on an avenue that dipped down, toward the buried center of this cone-shaped urban mountain.

And it was buried thoroughly, that center. Cooper soon left the upper layer of habitations behind, passing through a stretch of abandoned buildings with empty windows and no smell at all except for dust, and dust, and dust. Here updrafts whistled over broken glass and murky casements; if he’d been sober, Cooper might have turned back, but drink had given him a measure of courage.

Eventually the way overhead closed entirely and the street became a tunnel of rough bedrock that had been hewn and re-hewn over the years as the strange mountain grew. Daylight faded and was replaced by burning torches. Cooper no longer felt that he was in a city—he felt a hundred miles from anything, a lone intruder in a desert tomb, guided down, down, down into darkness. Water trickled from the walls, filtered by strata of history, sliming wet stripes of calciferous deposits onto the stone.

When he’d walked down for so long that he feared the ground must soon swallow him up entirely, the tunnel opened via a cataract of stairs onto a broad courtyard. Looking up, Cooper realized he had hit the center of the mountain, and stood at the bottom of a deep cylindrical pit, a small circle of sky providing light from far above. Cobbled with smooth marble, the courtyard seemed far too clean and tidy to belong to the archeological layer cake through which he’d just descended. At the exact center of the courtyard was set a large metal crest, but the image it might have borne had been worn away entirely.

What he saw next defied possibility. The circular wall of the courtyard was lined with archways, packed next to and atop one another: hundreds of façades, porticos, and gaping mouths of stone or brick were scrawled across the towering shaft, packed in one beside the other like books on a helical shelf. Cooper craned his neck to capture the scope of the place; drunken vertigo pulled at his gut as his eyes spiraled upward and he struggled to stay standing. Each darkened threshold stood starkly different from its neighbors—some were supported by massive columns, tattooed with scrollwork or crawling demons or formed from slabs of raw metal, while others were little more than clay bricks covered with paint and thatch.

Cooper decided that the archways looked most like the gaping edifices of religious monuments: countless temples, churches, and shrines. The doorways—of all sizes, from mouths of humble driftwood to the Brobdingnagian gates of pillared cathedrals—were stacked together tightly and coiled up the walls of the cylindrical shaft. Many of the entrances bore what looked to be some sign of divinity: a fat stone woman holding her own engorged breasts, the baleful glare of a steel mask, the branches of a bone-carved world tree; on and on it wound, a small infinity of architecture. Stacked one atop the other in no apparent order, the walls crawled with portals and doorways and thresholds, yawning empty and black. His head spun faster as he moved into the center of the space, standing on the worn metal plaque at its middle, like a navel.

The circle of sky hung distant, darkened but cloudless, a deep royal blue that seemed worlds away from the brooding umber sunset of the music fair he’d passed through to get here. Fragrant smoke of a dozen flavors poured from the many openings, scrolling upward toward the promise of starlight far above like a pilgrimage of ghosts. But Cooper could see that the darkened doorways were mere façades and nothing more—no vaulted tombs or flame-wreathed altars lay beyond their gaping doors. Cooper realized with nervous awe that he was standing at the bottom of an immense well lined with the faces of a hundred religions, scalped and mounted.

From above sounded the tolling of a bell, quickly joined by another, and another, until the whole sinkhole was ringing with the tolling of countless bells, an infinity of church towers converging above Cooper’s ears. He hiccupped and sat down hard on one of the wide steps that led into the well, bruising his tailbone. Even with his hands flattened against his ears Cooper’s head still pounded with the army of bells, while his vision swam and he felt he would soon be ill. On and on they rang, and even when the tolling began to cease the well vibrated with painful echoes.

Cooper held himself as still as possible until he could stand to hear again, the bells a second heartbeat in his chest.

“Welcome to the Apostery,” said a voice. “Where we bury our faith.”

The Apostery.

The name rang in Cooper’s head like a silver bell—the final note of the cacophony of the tolling he’d just endured—and he turned to see who had spoken. Something moved in the shadows. More than one thing, or one thing that made the sounds of many—a footstep to his left; the scuffle of gravel quickly silenced to the right; the quick sniffing sound of Cooper’s scent being tasted on the air. Something circled him.

Cooper saw it as it spoke again, a figure in black lurking beneath the lintel stone of a nearby archway. He tried to position himself with his back to a wall, but stumbled and half fell against a column while his vision spun. Cooper fought down panic.

“The Apostatic Cemetery,” the voice explained. “You came to hear the story?”

Then he slunk out from the dark, angling toward Cooper with predatory speed. His kohl-rimmed eyes were hungry and as black as the plugs in his earlobes, his body slant-ribbed and white where it showed through his tattered clothes. Despite Cooper’s fear, he was trapped, rapt, unable to move. The youth stepped close and drew back his arm as if to gut Cooper with a dagger—but when his hand sprang forward the light from above struck no naked blade but a poppy, sepia red and fresh.

Cooper blinked at the young man’s face, wondering if he could smell spilled beer. The stranger simply stood there, transfixing Cooper with his eyes.

He was a birthday magician, and Cooper the rabbit in his hat.

“For you,” he said with a smile. White teeth crooked at the center and a shy blush made his handsome face lovely. Beneath the slits in his shirt blue stars spread across his chest and arms, buffeted by tattooed winds and waves.

Iamthesailorsstarstoguideyouhome. Iamtwinstorms of airandwatertodrownandfreezeyou. Iwillhelpyou breathe when the sky has broken. Fear me, Cooper.

Cooper heard the words in his head but paid them no mind. His attention was focused on the pair of agate eyes gazing deeply into his own, as though the two of them were not standing beneath the glare of countless dispossessed religions, but were alone in a corner somewhere loud and smoky where nothing existed but two pairs of eyes and two pairs of lips, getting closer.

“I’m Marvin,” said the stranger as Cooper took the poppy from his hand. Their fingers touched; Marvin’s skin was warm and dry and felt for all the world like the most amazing thing Cooper had encountered since he arrived in this doomed city.

“I’m Cooper.”

Silence. Comfortable silence, Cooper had half a mind to notice. For lack of an alternative, he tucked the flower behind his ear. Marvin had another tattoo inside his lower lip, but Cooper couldn’t make it out.

“You came for the story?” Marvin asked again, more shyly, his earlier aggressiveness now evaporated in the face of, what? Something mutual. Something unexpected.

“Why are you talking to me?” Cooper asked, immediately wishing he hadn’t sounded so defensive.

Marvin looked as uncertain as Cooper felt, and Cooper wondered if maybe he wasn’t the only lost boy in this city. “I… I thought you looked like you could use a friend.” It didn’t sound very convincing, but it had the desired effect.

“Oh.” Cooper hung his head, now wishing he hadn’t taken the stein of ale and drained it so quickly. “I’m sorry. I just got here—”

“—I can tell—”

“—and I’m a little on guard, to say the least. I’m also a little bit tipsy. You said something about a story?”

Marvin nodded. “It’s all they do down here, tell stories. Since you’re new you wouldn’t know it, but the Apostery is one of the oldest places in the city. It grows all the time. Whenever a faith dies out, so they say. The pilgrims and locals both come here to remember the songs they used to sing, back when they had something to sing about.” Marvin thought about what he’d said, and made a face. “It’s kind of fascinatingly pathetic, I think.”

“Pilgrims?” Cooper asked as Marvin led him across the cobbled floor of the city’s navel, toward the only archway that was more than a shallow front.

“The Dying,” Marvin answered simply, as if that were obvious.

“That place is amazing.” Cooper marveled as Marvin led him past the opening of plain rock into another passageway, a darkened progress that led on beyond the well of faiths.

“That?” Marvin said. “That was just the courtyard.”

Nixon ran along the canal even though the edge was barely as wide as one of his feet. The other children wouldn’t dare, but it was the fastest way between Rind and Ruin south of Lindenstrasse, and Nixon couldn’t go into Lindenstrasse until the shops closed or he’d find himself hanging upside down from a thievespole. One too many apples snatched too boldly from the greengrocers’ tony displays had earned him a bad reputation in the neighborhood.

Nixon could cope with a bad reputation. Most of the other street children avoided him like the plague. Some were afraid of kids who did business, and that was probably for the best. The others, the ones like him… they ran their own rackets. If he’d learned one thing since he’d come to the city, it was to keep his nose out of other people’s games: impossible things happened here every day, and few of them were anything but awful.

And yet, the City Unspoken had given Nixon a golden opportunity for what he considered quite possibly the finest grift the metaverse had to offer: juvenile reincarnation.

It was true that without intervention of some kind, the soul of a person who died would transmigrate elsewhere, guided more by its own incurable nature than any cosmic plan, and would clothe itself in flesh that reflected the spirit’s own self-image. Nixon represented one of the variant incarnations. Not the kind of folk who were just young at heart and tended to incarnate very young—no, Nixon and his fellow juvenileincarnated anomalies were sick jokes: murderers and rapists and thieves of every caliber—generals, popes, and greedy opportunists. In a way, Nixon suspected that the young bodies into which they’d been incarnated represented an ultimate deviance of the soul—they may not see themselves as children, but each and every member of his loosely aligned group of reborn unboys and nongirls intuitively grasped the advantage of starting new lives dressed in the bodies of cherubs: it was the perfect scam. Less ambitious pseudochildren found employment between the sheets, but to Nixon’s eye that was a life better suited to the city’s three kinds of whores—the possibilities presented to a canny mind in a child’s body knew no limit.

Take his current errand, for instance. The job was simple enough, but no regular kid could handle the employer.… Nixon scampered a little faster along the canal wall. It would not do to be late returning to the abandoned room, and the meeting should be over quickly enough— the ass end of a spy job rarely took long. All he’d need to do was nod. “Yes ma’am, miss crazy hair, I saw him, ma’am, clear as cut crystal.” Then grab the money and run.

It was true, Nixon conceded, that there might be more glamorous or powerful lives to live—the endless bloody deaths of a Coffinstepper, for instance, hunting dangerous quarry across dozens of realities at once. Or the days of a plutocrat noble ruling a city with a stranglehold on the ultimate commodity. Those might be thrilling lives, but they weren’t his. Not yet.

Nixon leaped over the boundary fence at the end of the canal and landed on Ruin Street without a sound. He dropped into a patch of sunshine, the street around him empty. The sun still shone overhead—the sky wasn’t sane yet, but it was on its way, and Nixon took a few seconds to enjoy the heat on his face and chest. That green sun would go away, he could feel it, and an honest sky would take its place. From Nixon’s vantage, the strangest thing about the City Unspoken—which was saying something—was its variable sky. Depending on the mood of the firmament, you’d wake up to any number of possible skies, and if it hadn’t changed by lunchtime, you counted yourself lucky.

He patted his tan little belly and pictured the meal he’d buy himself with the coin he’d earn today. He pictured the sun he’d eat it under. Imagine that, Nixon marveled: honest coin, a yellow sun in a blue sky, and meat in a bowl at the end of the day. Life was good.

He passed the building with the blue door and shimmied up its gutter to the second-story window, where the red ribbon was tied around a bent nail sticking out of the casement. The window was still open, and Nixon pulled himself into the abandoned room with a brave face. He wouldn’t let his legs shake this time, he promised himself as he felt his way through the boarded-up room and into the deeper darkness beyond, no matter how pretty the lady was, or how she burned the air just by standing in it.

When the sudden flare of a lantern splintered the darkness, Nixon barely suppressed a squeal.

In the hallway stood a small woman with a sweet face and red curls, who hung the lantern on the wall and smiled at Nixon. She wasn’t wearing any shoes, just a faded shift, and there were far more curves exposed than Nixon was usually allowed to see. A ribbon as red as the one on the windowsill adorned her ankle, and she lifted a lovely foot off the floor just slightly.

“Did he come?” she asked. Her red hair moved like clouds across the sky, though the air was still.

“Who are you?” He asked the question before he could stop himself. And what do you care about the gray hippie picking up some portly stiff?

“Did he come?” she asked again. Nixon had the feeling this woman possessed extraordinary patience, but he couldn’t say why. She felt too real, was all he could think—the hairs on her forearm, the pucker of her lips, it was as if the rest of the world were a grainy film reel and she, a true woman, had stepped in front of the screen. Thing was, Nixon was pretty sure she was anything but a true woman. There were things that looked like people, he’d learned, but weren’t. Things that might even convince you they were gods—but they weren’t that, either.

“I mean it,” he insisted, “I really need to know who you are.” He didn’t, but he wanted to be able to lord this story over the other gutter rats, and how could he do that if he never found out the identity of the slight little thing who brimmed with power?

“If you’re worried about the rest of your money… don’t be.” The woman handed Nixon a little wooden box, and he peeked beneath the lid. It brimmed with nickeldimes, easily twice as much as he’d been promised.

“He came!” The words were out of Nixon’s mouth before he could stop himself. He held the box behind his back and retreated a step toward the exit; his curiosity evaporated in the face of cash.

A Cheshire grin lit the barefoot woman’s face, brightening even the abandoned building that decayed around them. She did a little dance and held her hand out in an invitation, one eye shining in the torchlight, the other dark. Nixon hesitated, then tentatively put his small brown hand in hers. Her skin felt feverish-hot and cold as the vacuum of space, and for half a moment her bright eye blinded him as the darkness in the other yawned vertiginously.

She pulled the length of red ribbon from her ankle and tied it around Nixon’s thumb. “When you see him again, I want you to do me one little itty-bitty favor. I want you to give him this. He’ll be new and untrusting, but I want you to do it anyway. Use that disarming smile of yours.” Dropping his hand, the being shaped like a redhead stood back and admired the boy as she might admire a puppy in a shop. “Will you do that for me?”

Nixon wasn’t listening, which was nothing new. Then he snapped himself out of it and nodded with an earnest grin even though he didn’t follow her logic—any newcomer should be untrusting, and what would he want with ribbons?

“You’re a spicy one, aren’t you?” she asked with a trill of a laugh. Nixon didn’t know what she meant by that, either, so he looked at his feet. When he raised his eyes, he was alone in the hallway with a lantern and a ribbon and a boxful of dinner.

The Apostery was as vast inside as it was outside. For a long minute the only thing Cooper could process was the hugeness of the space: a vaulted cathedral ceiling soaring higher than any he could recall seeing before; massive support columns the girth of small houses rising into the darkness above, etched with names and signs, inlaid with silver and steel; smoke-stained wheels of candelabra dangling from chains as thick as his torso; and the light—the light that came streaming from all angles ahead, slanted on an angle that caught in the air, veiling the enormity of the space in serene curtains of dust and smoke that wafted through the air, unlike the barometric fumes that billowed up the well of the courtyard. Any bishop would give his favorite catamite for a place of worship like this. But this, Cooper began to understand, was no cathedral—rather a mausoleum. A grave for buried gods and the stories they told.

He and Marvin walked toward the light, their footsteps the only discernible sound in the enormous space. As they grew nearer, he saw past the columns to the source of the light, and that was the real glory. As the Apostery’s courtyard was a vault of doorways, here was a court of windows—stained glass portraits ringed about the walls and rising in layers to the ceiling. It appeared that the mountain was hollow. Each picture captured the likeness of some being—gods, it could only be—of every sort imaginable and more. A blue woman with severed breasts and eyes like sapphires glared down from a throne of ice; a man with stag’s horns crouched half-hidden behind a mask of leaves; a gray sword, point down, with garnet eyes staring impassively from the quillon. Panes of gold glass as tall as sequoias stretched upward beyond sight. On and on the windows shone, each more artfully worked than the next, and each was lit from behind as if by perfect afternoon sunlight, although it was evening already, they were far underground and, in any case, the sun could not possibly be in so many places at once. The light filled the air now, shading its smoke-strata a hundred colors.

“Apostery.” Cooper repeated the name like an invocation. “Apostatic? You said? Like an apostle?”

Marvin shook his head. “Like an apostate. I told you, these people have nothing left to believe.” Marvin indicated the visitors who sat with their own thoughts or strolled from window to window. “Atheism is the traditional faith of the City Unspoken. When your own persistence disproves the truth of every religion you’ve ever encountered, churches lose their punch. Hence the Apostery—the Apostatic Cemetery, where we mourn our lost gods, whether they were real or not.”

Marvin steered them to an alcove off to the side, beneath a clerestory where a small group of people milled about. They joined the others and Cooper smelled the familiar scent of a campfire. He craned his neck and saw the reason for the gathering.

An old woman sat on a broken column, warming her toes over a fire tended by those gathered around her. The crowd bore many faces, and Marvin whispered to Cooper that he might even recognize some; they hovered near the fire pit—there were eyes faceted like gemstones, antennae and feelers and protuberances aplenty; jawless tongue-flapping faces; viridian and scarlet and mauve faces; fey-touched and bedeviled faces.

“The usual stuff, if you get around,” Marvin explained, nodding at the more unusual-looking people. “Which, of course, you will. Eventually.”

One feature every face shared was a certain flavor of anticipation, a kind of lonely hunger. And patience. Patience, because many of them had heard the old woman tell her stories before and knew it would bring them a measure of peace; those who had not heard the story had traveled far and long to hear it, which was why the faces of this gathering were stranger than those Cooper remembered seeing in the city above, and although they might not know that it was this particular story for which they had come, they had all learned patience along the way and gained the knack of sensing important when it was near.

Are these the Dying, then? They seemed nothing like the crazed man who’d assailed him earlier on the streets of the Guiselaine.

Only a hooded woman at the other end of the gathering seemed impatient. She tapped a pencil against a pad of paper, insistently, and pursed her lips. Pursed lips were all of her face that Cooper could see, obscured as she was by others, but he wished she’d stop tapping that pencil.

The old woman looked something of a scoundrel. Something about her seemed different than the others, as diverse as they were—a smile that lived in her eyes, a kind mischief crouched in her wrinkled mouth. Her sparse white hair braided with beads and bolts and bottle-caps, she smiled at the pencil-tapper. Cooper imagined that she would draw this one out, just because she could.

Eventually, after much tapping of the pencil, the old woman gave a conciliatory nod and began speaking. Her voice was strong and clear, not at all what he’d expected.

“Sataswarhi, hear me; be my midwife in the birthing of these words.”

Marvin leaned in close to Cooper and whispered, “She is Dorcas, an elder of the Winnowed, a tribe that live beneath the city. They’re rarely seen aboveground, but they send elders to the Apostery to tell a version of this story from time to time. It’s never even remotely the same.” Cooper heard the words and drunkenly processed something about an underground tribe and stories of debunked deities, but all he could focus on was Marvin’s clove-scented breath hot against his neck. He wished it would move closer.

The elder Winnowed continued:

“Sataswarhi, heed me; I call you up from the depths beneath the crust of the worlds.”

The hooded woman had stopped tapping her pencil and was hunched over her pad, scribbling. Cooper’s head spun.

“Sataswarhi, help me; there is more weight in this story than my voice can carry without your touch upon my work.” For a moment the old woman hesitated, looking up at the towering windows as if they were old friends; she smiled at her stained glass family. Then she explained herself:

“Storytelling is my contribution to the Great Work in which we are all instruments. This is a story our people tell about the origin of our city, not a tale of gods and goddesses. It is not a real story, but it carries some truth. Perhaps.

“Sataswarhi. Clear Star of the First People, the origin and namesake of the celestial river that flows from above down through every land, from the most distant dim heaven through every isolated cosmos until it spills, here, beneath our feet. Far below the source of the river lies its mouth, where the waters empty into the void beyond creation. Here.” The old woman, Dorcas, pounded her perch with a shriveled fist.

“Here did a tribe of the First People build a city. They named it, as it has been named and renamed ever since, again and again—until, like the snake that swallows its own tail, there was nothing left to hold a name. Today it is simply a city, and we call it as we like; we curse it or praise it according to our mood, but we know better than to ask its name. It is sometimes easier to live with a thing when you do not know its name, especially if you do know its nature.

“However, this is not a story of the nature of the City Unspoken as it sprawls and oozes today. This is not a story of our time, the time of the Third People, we who comprise what the shortsighted call history.” A careful flick of the eyes to the woman with the notepad. Would the notetaker know that the tale was only one version among many, crumbs scattered for the faithless flock? “Nor is it a story of the Second People, whose crime was so great that nothing remains of them, as everyone knows, neither bones nor stones nor names. This is a story of the First People, the bright and dark ones who were born in the crucible of creation, who are the direct children of the Mother and the Father, born of Their destruction. They who are the children of the dawn.

“We only ever had two Gods, and They murdered Themselves to give us life, and it was terrible. A thing to shatter galaxies, if there had been matter or gravity then. When the storm of shadow and light had passed into mere turbulence, when the worlds first coalesced from the divine fallout of the Apostatic Union, then did the First People open their eyes. They rose from the dust and glitter of the worlds, or they gasped their first breaths in the ether between universes, that starless stuff which is empty yet always full. Wherever they stirred, the First People shaped the worlds around them. Some were great, and pulled the fabric of existence behind them like a heavy cape as they moved; it is true that some few of these still persist today in one form or another, disguised at the edges of our lives as gods or demons or half-whispered nothings that caress our hearts in the darkness. Many of the First People were not great, however, but lived much as we do, which is to say they depended upon one another. Community. They came together for shelter and solace, for survival, and so they laid down the foundations for everything.

“They built the first cities.”

Marvin elbowed Cooper. This is the good part, so listen up. Cooper might have wondered why Marvin’s voice in his head was clearer than before, or how he knew to think at Cooper rather than whisper, but Cooper’s attention was so finely divided between following the story and trying to resist the further-intoxicating scent of his new guide that these arguably more important considerations were, for the moment, beyond him. He thought he might need another drink soon.

“Now of the great ones, there were many who found no interest in their minor siblings, and those who took interest often did so for less than generous reasons. The smaller children of the dawn could be fed upon, or manipulated and amassed into armies of soldiers or servants, or simply toyed with for the amusement of their more powerful kin. Still, there were a handful who were both great and kind, and it is to these— where they have endured—that the most lasting monuments, mythologies, and blood-memories are dedicated. There is Chesmarul, the red thread, who is called first-among-the-lost, who others claim was the first daughter of the Mother and Father and witnessed Their destruction with her own new-wrought, tear-stung eyes. There is the Watcher at NightTide, who does not condescend to speak his own name but bequeaths knowledge to those with the mind to seek it and the fortitude to withstand it. Another is his father, Avvverith, inscriber of the first triangle and all that sprang from it—all things which come in threes, including architecture, which is idea written in three dimensions.

“This is not a story about Chesmarul, although we suspect she is always with us, after her fashion. Neither is it a story of the Watcher, even though it is his nature to observe all things. Avvverith Sum-of-Square gifted the lesser First People with the tools they used to build their cities, but has ever since been absent, so this cannot be his story.

“Instead we turn to Sataswarhi, the Clear Star, who made her home atop the ceiling of the heavens where she could look down upon all the worlds, all the baby universes exploding and expanding in their own pockets of space. She is said to be the source of all art, the inspiration behind inspiration. Not a muse as some consider the notion, not a passive beauty that turns men into dreamers—Sataswarhi is the active catalyst that turns dreamers into doers, poets into bards, wonderers into wanderers. From her home at the apex of creation a river flows, it is said, that touches upon every world in every little universe at least once. How it winds and where it turns are unknown quantities, and the legend tells us that in these days of the Third People, the river Sataswarhi flows still but is buried beneath aeons of rock and ruin.

“Of one thing we are certain, both then and now, that the river Sataswarhi begins at the highest point and ends at the lowest, the nadir, that land which sits like a drain at the bottom of creation, where all things must eventually find themselves before they pass out of existence and into oblivion. It was at this sacred but troubled place that the First People built the original incarnation of our city, fashioning a series of great gates encircling one another, a maze of concentricity crafted of diamond and gold, something bright to raise the spirits of the Dying as they made their pilgrimage. Here the First People built a fortress around a threshold, beyond which lay True Death.

“Now, listen closely; this is important. Although if you are here, you must know it already. It bears repeating.”

Now. Marvin thought fiercely. Magic voices sound louder when you’re a little fucked up, Cooper noted.

“There are many deaths, some larger than others. We are born only once but die many times. Each death is followed by an awakening on a distant world, where one lives again until another death comes to ferry the spirit across the void toward the next step of one’s own journey. This is life; this is what it means to live. We are born, and we live. We find ourselves and lose one another only to be reunited somewhere most unlikely, for although the worlds are finite they are of nearly infinite variety—some are cold and lifeless; some are bright but blind to the teeming others which surround them; many are rich in magic or invention, or both.

“There is only one common destination shared by everything that is born, and that is the City of the Gates, which we inhabit today like squatters in an abandoned mansion—eventually, all things that are must come to this place so that they can attain iriit and cease to be. It is the cloaca of the metaverse, the Pit, the Great Drain, the Exit.”

“Iriit?” Cooper whispered, but Marvin shushed him. Cooper tried something new—he flexed a muscle in his head and thought, somehow, loudly: What is that?

An older word for True Death. Marvin thought back. What makes this city famous. For the first time, Cooper became conscious of the fact that he did not hear any fear in any of Marvin’s thoughts. What made Marvin different?

“You may believe the river Sataswarhi is the blood of the Father-god, or the spirit of the Mother-goddess; you may believe it is only a metaphor for the processes of life and death; you may even doubt its existence entirely, and choose to believe that it is a myth cultivated to aggrandize the City Unspoken and its cash crop, True Death. My people, who live beneath the city where the old waters still flow, share these opinions and more besides, even though it is the river—well, a river—that sustains our troglodyte lives.

“And while the Winnowed venerate diversity of belief and nonbelief, living far beneath the streets of the city has given us an unusual education regarding its long-forgotten beginning. We make our beds beside the cornerstones of the founders, architecture long ago buried but still recognizable as the handiwork of the group of First People who built here—not the scattered poseurs of this era who masquerade as deities, or ply their petty schemes, or find refuge in distant worlds—but a people who lived as we do.

“We recognize the authority of no gods, but we approach worship in the reverence with which we see the footprints of the founders of the city. What stone survives tells us only enough about them to appreciate the depth of our own ignorance. They named their tribe ‘aesr,’ and appeared as brilliant-skinned people whose flesh was made of white light; they had only one eye, or perhaps four; proud crests topped their scintillating heads that might have been ornamentation or part of their anatomy; their limbs were arms and wings, and they tended to a grove at the heart of their city-maze that, I believe, was itself the remains of a primeval forest that covered the land during an even earlier age.”

Cooper tried to picture the creature the Winnowed woman had described. What would he say to such a thing?

“The First People of the city—the aesr—had no king, but were governed by a prince; this much alone seems to have survived although the rest of their lives have been overwritten a thousand thousand times by the palimpsest feet that have walked the streets of this city throughout its history.

“What became of our founders remains one of the city’s greatest mysteries. If the scale of time were less vast, we might know their fate—did they vanish or perish, did they file through the Last Gate? Did they Die at once or did they slowly become extinct? Did they travel elsewhere? What we can say for sure is this: they are gone, save one. He who ruled this place, the monster of light who locked up the nobility inside the Dome, and then fled.

“All that is left aboveground, tangibly, of the greatest of the cities of the First People now sits within a Dome half as big as the sky itself, the seat of our prince, last of his kind, who until recently maintained his lonely vigil over oblivion, as his kind have done since before we acquired memory. This is why we must have faith in the face of recent events: it is the prince’s charge to protect True Death, for it is essential to the cycle of life on all worlds. What is born must die. What is here today must be gone tomorrow, or the next morrow, or the next. Like the river Sataswarhi, our lives must eventually empty into nothingness to create room for the waters that rush behind us. Otherwise comes the svarning.”

The hooded woman gasped at the word. Cooper looked at her more closely now, and noticed the unmistakably pink hair she’d begun twisting around her pencil. Why was Sesstri here, and had she seen him? Why had she gasped? He took a half a step behind Marvin, hiding. It was unwise, he knew, not to run to Sesstri and beg her for help, but he held back. She’d probably ordered Asher to get rid of him, for one thing. And then there was Marvin, who smelled like rum and smoke.

Old Dorcas faltered, looked confused, as though she’d forgotten where she was or why she was surrounded by her audience. Then she shook her head and finished abruptly.

“If the Last Gate closes, then we will all drown.”

The barest hint of a susurration passed through those who stood listening. There were glances of acknowledgment tinged with something that resembled alarm. From his perch behind Marvin’s shoulder, Cooper saw that neither Sesstri nor the Winnowed elder failed to notice the crowd’s reaction. They held each other’s eyes for a moment, and both looked haunted.

Marvin cocked his head back and rubbed his scalp against Cooper’s ear, then craned his neck until their lips almost touched. Again, he spoke without words: Don’t you believe that, because it’s a lie. The end of True Death would mean freedom for us all.

Twirling a piece of red string knotted around a loose dreadlock, the crone continued with her story. Marvin snaked his arm around the small of Cooper’s back, leading him away from the gathering. The old woman’s story vanished from his thoughts with Marvin’s touch, and it was all Cooper could do to keep his knees locked and his body upright. They walked toward the courtyard in a lusty haze, and through the drunkenness he felt electric fingers on his spine, testosterone sweat perfuming his thoughts with sailor tattoos and black gutta-percha earplugs, the promise of full lips and two bodies crushing together.

Then talons tore into his shoulder and spun Cooper around like a puppet. Sesstri’s other hand yanked his wrist and pulled him away from Marvin.

“What. Are. You. Doing?” she hissed. “Don’t you know what he is? And where the hell is Asher?”

The bitchiness in her tone brought out something that had lain dormant in Cooper throughout the whole day. He withdrew from her touch and lifted his chin, remembering her words that morning, when she’d been an angel cradling his head in her hands.

“What the fuck do you think I know? How could I know anything?” He spat—actually spat—in her face. “I’m a turd, remember?”

Sesstri had the good sense to hold back her anger but gave no sign of remorse or sympathy. She left the spittle to dry on her cheek.

“This animal,” she pointed at Marvin, “will drag you back to his cohorts, who will rape you until you cannot remember your own name, force you to pollute your soul and offer it up to their masters. Know that, when your lips have been bitten off and you can’t spit in any more faces.”

She’s lying. Marvin thought at Cooper. And you know it.

“You’re wrong.” Cooper didn’t know it, but he knew he was furious and he let the rage speak for him. “You insult me and abandon me and then assault me when someone gives me a moment of basic human decency? Who do you think you are?”

Sesstri grabbed him by the arm and stalked toward the exit. “I’m the only chance you have at saving yourself, Cooper, and if you’d stop behaving like a brat who needs a spanking you might even understand when I explain why.” Light from the courtyard streamed in through the incense smoke, and Marvin followed at a clip.

“And if you weren’t such a stuck-up cunt I might even listen. Fuck off and die, if you can, and wake up somewhere far away from me.” Cooper threw off her hand and stumbled into the starlight—overhead, the sky lit the well of faiths with a blue glow. He ran a few yards and tripped over the metal crest set in the center of the courtyard floor. Milling apostates looked at the commotion with annoyance.

“If I can?” Sesstri laughed, a bellyful of sound that didn’t belong in her wasp-waisted frame. “Cooper, you bumbling disappointment, you have no idea how close to the mark you’ve hit. And unless you calm down and listen to me you will wish you could die and wake up anywhere else but here.” She reached into her satchel and brought out her notepad, as if to read from it.

Cooper smacked it out of her hands.

Sesstri let the paper flap in the incense and stared at Cooper hard. “Have you even looked at your stomach yet, Cooper?”

“Have I what?”

“Are you drunk?” Sesstri asked with an escalation of incredulity. “I mean, honestly, Cooper, button your pants and open your eyes. You need my help, not a cuddle.”

Cooper turned from her and saw Marvin’s lip tattoo clearly for the first time—just inside his lower lip a black coin had been inked, with a stylized snake of negative space slithering forward as if wriggling out of Marvin’s mouth. The light was far too dim for Cooper to have seen, and anyway the inkwork was a rough job, but somehow Cooper’s eyes picked up the detail, and he did not question why. For a moment Cooper saw the tattoo more clearly than could have been possible—he saw that Marvin held a coin in his mouth, and a tiny green snake crept over it, a forked tongue darting out like an extension of Marvin’s own. Then the overlaid image vanished.

What was that? he wondered, passingly.

“Your lip,” Cooper said, scowling at the coin and snake. The tattoo hardly looked friendly. “I don’t… I don’t think I like that.”

“It’s his slave brand,” Sesstri sneered. “The symbol of his masters and the sign of his enslavement to them. He’s a goon, Cooper, stationed here to cull the unwary and those enchanted by the promise of True Death.”

“That’s a lie!” Marvin challenged her.

“Oh really?” Sesstri was smug. “I suppose you’ll tell me that tattoo on your lip, whatever it is, is not the symbol of your bondage to the Undertow, and you aren’t a runner for a gang that worships lich-lords who swarm unseen above your burning towers? You aren’t in thrall to undead remnants who steal souls from the dance of lives and bind them in torment? Who rape children to taste purity?”

Marvin cursed beneath his breath and took a step back. Cooper stood bewildered.

“That’s not right,” Marvin began, but his protest sounded feeble. “It isn’t torment to be free.”

As he pleaded, other figures emerged from the shadows above. Black bodies like boomerangs jackknifed overhead, whooping, flipping from portal to portal and swarming the air. Landing like maleficent dancers, young men and women wearing dark clothes hit the pavement stones rolling, tumbling, screaming laughter and manic smiles. They all looked like Marvin. A thin girl rose like smoke out of the shadows behind Cooper; two boys leapt over his head, caterwauling, and pushed off from each other, spiraling to the ground bare of chest and foot, wearing only silk trousers. Around him, devout apostates scattered inside while casting dire glances over their shoulders. Cooper heard chirrups of their fear as the pious impious flapped away: UndertowOverheadUnderfoot NoPeaceNoPeace…

“Oh for fuck’s sake,” Marvin groaned, reaching for the wrist of the thin girl. “Couldn’t you have held back for a few more seconds, Killilly?”

But the girl spun out of range and grimaced. “Shove off, Marvin. Can’t you see it’s not going to happen? Slake your lust with Hestor as usual, and leave the thighs of this full-figured insect alone.”

Marvin looked away.

“Do you still feel like fondling strangers, Cooper?” Sesstri sneered at Marvin, who narrowed his eyes but said nothing. “This boy works for the undead. Do you want to discover yourself trapped in the lair of skeleton wizards who drink innocence like wine? Do you want to be their slave? Their meal?”

“Don’t listen to her,” Marvin said to Cooper. “Come with me and you’ll see freedom.”

“Or don’t, and save yourself from mutilation.” Sesstri’s tone was casual. “Asher and I can help, Cooper. You don’t need to resort to trash. Don’t be stupid.”

“Come with me,” Marvin begged. Now.

Marvin’s sad eyes and full lips were a siren song, and Cooper wanted so desperately to make himself inseparable from those lips, the smooth skin of that body, muscle and hair and spit. But Sesstri’s warning was hard to ignore, and she wouldn’t warn him if she cared as little for Cooper as he’d thought. And where did sirens lead you, but the rocks? He didn’t have enough information to make the choice. Cooper didn’t make a decision so much as follow an instinct he usually ignored:

“No,” he said. It was his word, and it felt good to finally say it.

He turned on his heel and ran, the blood in his head already pounding out a rhythm of escape. He pelted out beyond the courtyard and was sprinting up the tunnel to the surface before either Sesstri or Marvin could say another word. He felt bells ringing in his head like a thousand sermons, urging him to run faster, faster, away from the—the what? For a moment the chaos of bells and tears buzzed into a kind of white noise, which in turn collapsed into a high-pitched hum, then fell quiet. Cooper ran from Sesstri and from Marvin and from their dueling falsehoods, and he could feel their focus on him like raptor eyes.

Don’t leave! and Not yet! cried their unconscious fears. And from Marvin a second, deliberate whisper into the language centers of Cooper’s brain: I’m not what she says I am. Cooper sobbed and ran faster, bells still tolling all around him.

Through a haze of tears, he ran out from under the mountain, through the music, and back across the bridge of titan bones and rebar. He fled the bells, past the wet spot where the fighter pilot’s barrel had been, and past the footpaths that led over the canals into the Guiselaine, where Asher had abandoned him—he wouldn’t go in there, it was dark now and looked ominous. So Cooper darted down unknown streets, barely drawing notice from the jaded citizens of the City Unspoken, until at last he collapsed outside a three-story tenement in a filthy square, where the only sound was children playing cruel games, and all he could think about was home.

The Waking Engine © David Edison, 2014